June 24, 2018.

That was the last time I blogged at Interpolations. It’s been a spell. I’ve been happily (and productively) engaged on other fronts. In the last five years, I’ve continued reading, always. Too many books to name, although I’m likely to share one or two titles at the end of this post. Well, because.

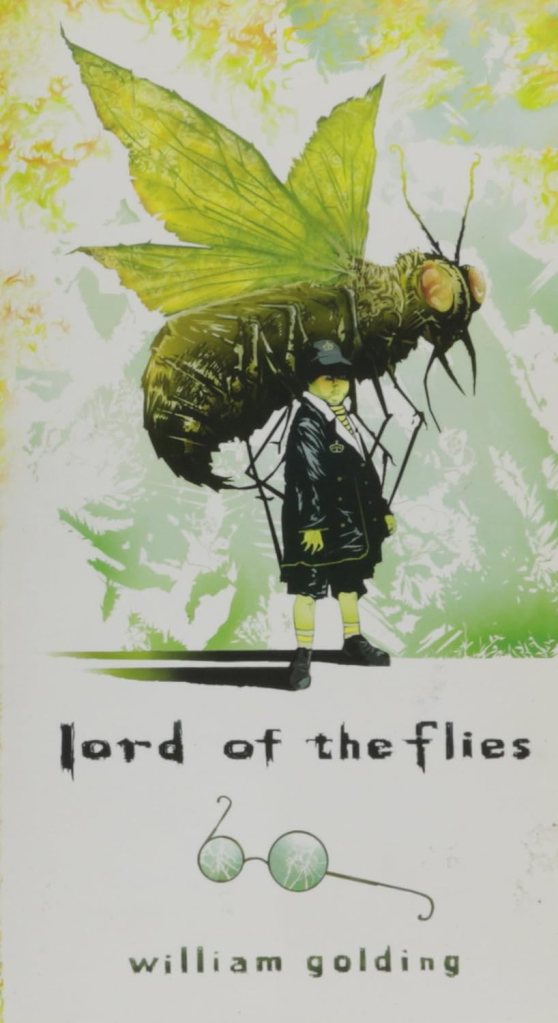

Recently, I re-read the Lord of the Flies with my son. Holy smokes, what a book! I can’t think of a novel that explores a grimmer theme. Wait, grim isn’t quite right: malevolent. That’s better—malevolent, ghastly, wicked, evil. Moby Dick doesn’t even come close. Nor does Blood Meridian. And not even the Bible. Lord of the Flies stands alone in my mind, as the most artful treatment on the origin of evil in individuals and society.

Of course, I read the novel in high school. I remember Ralph, the fair-headed boy, a decent kid. I recall Jack, the id-beast in handsome human form. And of course, I remember Piggy, his plump far-sighted frailty. But I had no recollection of Simon whatsoever. His character hits me now like a revelation, as it should, given his role in the novel.

Unlike Jack (brutal appetite), unlike Piggy (bespectacled reason), and unlike Ralph (ineffectual pragmatist), Simon (a “batty” mystic) is the only one who perceives the nature of their condition. But his perception is ineffable, as most mystical perceptions are. Unable to adequately communicate his insight to others, he’s brutally murdered by a group of boys in the grip of hysteria.

When a bunch of kids butcher a mystic, it’s pretty damn gruesome. But Golding takes the gruesomeness even further. He populates Lord of the Flies with Christian symbols. They abound, everywhere. They’re as prolific as the creeping vines that choke the forest. Symbols of innocence, fallenness, sin, rage, lust, ignorance, will, desire, etc. Etc. Every major symbol in Christianity can be found in the novel save one:

A symbol of a loving personal God who’s interested in your fate. God is absent in the story, and that’s by design.

Golding’s religious awareness—he regarded himself as an “unaffiliated” Christian—is perfectly consistent with a godless world filled with sharp teeth and claws and rotting flesh, a world of demented social norms and savage individuals. Lives shimmer over a cauldron of blind indifference. At the end of the novel, the boys are rescued without being saved.

Therein lies the dark pessimism of Golding’s vision.

No, I haven’t forgotten

I teased two titles above, and now it’s time to deliver. Two books stand out as being exceptionally good. Actually, three. I forgot: there was a third.

Bereft of commentary and sitting on nothing more than my three-legged authority, I highly recommend The English Teacher by R.K. Narayan, A Month in the Country by J.L. Carr, and This House of Sky by Ivan Doig. I found the two novels and memoir, respectively, incredibly moving. Do shortlist them.

I have an idea for a future blog post at Interpolations. Think I’ll sit on it for a while.

See you in five years, I hope.